Although the surgical procedures is not the focus of this blog, I would like to share with everyone a new technique that we are performing in our practice. The majority of ankle sprains do not require surgical treatment. In fact, most athletes are able to return to running and competition within 2-3 weeks of an acute ankle sprain. Even a severe sprain can go on to an almost normal recovery. Sometimes however, the condition becomes chronic which typically occurs over several years. One usually encounters sprains of the ankle by just stepping of a curb the wrong way, or even periodically during a season of competition. When this occurs, your ankle may be inhibiting you from performing the activities you otherwise would be able to do. Surgery is usually indicated at this point.

In the past, surgery typically involved a primary repair (tightening of the ligament itself) or a secondary repair (utilizing the patients own tendons to recreate a ligament). While these procedures work well, they do have some complications. The primary repair which involves tightening the ligament itself, is only as strong as the ligament that remains.

There are numerous variations of secondary repair most of which involve harvesting a portion of the peroneous longus tendon and using it to augment and/or recreate the ATF and CF ligaments. When the peroneous tendons are sacrificed for utilization in repairing the ligaments, the tendon itself has to undergo a healing and repair process adding to further swelling and pain post operatively. In essence, not only does the ligament repair need time for healing, the disrupted tendon now has to heal and repair. It’s almost as if the patient is healing two procedure instead of one.

Secondary repair involving harvesting a peroneal tendon for recreation of the lateral ligamentous complex.

The technique performed on the patient in the video below involved recreating of the ATFL and CFL with the use of a product known as Fibertape by Arthrex. Fibertape is an ultra-high strength suture material that is anchored into the bone at the sites corresponding to the attachments of the ligaments. A corkscrew anchor provides a tight fit resisting the ability to be pulled out. The Fibertape is described by Arthrex as being an augmentation to the existing ligament, but in actuality it is much stronger then the body’s own ligament tissue and provide more support then just augmenting the ligament itself.

See the video below revealing the improvement in strength of the ligaments and minimal swelling at just 3 weeks post operatively.

Part 1: Lets Get Started

This series is intended for someone who has never ran before, someone who wants to get back in running after being inactive for a period of time, or someone needs to reset their running.

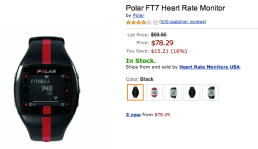

What most people who have never ran seriously before don’t realize is they don’t need to “kill themselves” with each run. Even the elite marathoners do not run every run hard. 80% of your weekly mileage should be at an easy pace, and this is only if you are training for a race. If you are just starting out or building a base, then all of your runs should be at an easy pace. What defines an easy pace? It should be conversational. Meaning you should be able to carry an entire conversation without stopping to take a breath. A more scientific way is to wear a heart rate monitor and run at your “aerobic rate”. This can be found by subtracting your age from 180 and was established by Dr. Phil Maffetone. Maffetone trained many elite athletes and even helped Mark Allen win six Ironman Events, with the last being at age 37! For example, a 35 year old would be training at a heart rate of 145 or lower on all of their easy runs regardless of the pace. This will help build ones aerobic fitness and eventually their pace will improve but at the same heart rate. So one may be running at a 10:00 to 10:30 mile pace beginning this type of training, and by 4-6 months into it they may be running 9:30 to 10:00 miles at the same pace.

Several things to consider

Beginning Runners

Do not let speed or pace deter you from running, regardless of what pace your fellow runners may be running. Your goal is to keep your heart rate in the appropriate zone. If this means walking, then you need to walk. Walk 2 minutes, then run 2 minutes. Focus on your hear rate and eventually you we will be running more then waking. Start of with 30 minutes of activity and progress to one hour. You will first obtain 30 minutes while running them progress to longer activity. Remember, your goal is not to see how fast or far you an run, but rather to sustain your heart rate in its aerobic zone for up to sixty minutes. This will build cardiovascular endurance making you a better runner, as well burn more fat. The ability to burn fat while running slow is a topic for another discussion but one will burn more fat running slower then harder.

Seasoned Runners

As many runners head out the door, they have a predetermined pace before they even start their run. This can be problematic because pace is not a true determinant for gauging how “hard” you should be running. By using the “no pain – no gain” philosophy, your body becomes vulnerable to overuse and eventually can become injured. Many runners have a goal of becoming faster and think they need to run faster to accomplish the. This is definitely NOT TRUE! I have made this mistake and have also witnessed countless runners do the same. Slow down! I have seen runners PR in a 5k by simply adding mileage and slowing there pace down to an aerobic pace. If you are reading this and currently have been running half marathons or marathons and just can’t improve your time regardless of how fast and how many 800 and mile repeats you are doing- I suggest you slow down. Slowing down and running at your aerobic pace will improve your efficiency in 3-6 months. While this may seem like a long time, it is not. I tell many of my runners that the most important part of any marathon training program is the 6 months leading up to it.

Answers to questions you may have from what I has been discussed here can be found in most of my blog posts. If you want to ask a question, please feel free to do so in the comments below and I’ll do my best to answer all of them. Try tweeting me as well! If I’m in between patients you may get a quicker response!! @runnerdoctor

Just an interesting article I stumbled upon and thought everyone might enjoy….

(Photo: ABCnews.go.com)

Running used to come with street cred. You got the head-clearing glory of those pre-dawn miles and plenty of fitness prowess was conferred upon you for it. Now, it seems everyone who laces up their sneakers is upping the ante and training for a full-blown marathon. When did running 26.2 miles become the brass ring of fitness? And should it be?

“I feel like everybody does marathons now,” observes Jess Underhill, a New York City runner, coach, and founder of Race Pace Wellness. “Most of my clients are working towards marathons, and if they’re not, they’re on the fence about it.” If you’re a runner, you’re a potential marathoner, the thinking goes.

The numbers reflect that sentiment. According to Running USA, in 1980, 143,000 people finished marathons in the United States; in 2011, that number rose to 518,000. In New York, about 15,500 more pavement-pounders finished the ING New York City Marathon in 2011 than 10 years earlier. And while the country debuted 550 new marathons between 2000 and 2012, getting a spot in one is often like trying to score a ticket to see Lady Gaga at MSG.

“There’s a stigma now if you’re a runner and you haven’t done a marathon. People that aren’t running marathons feel inferior,” says Jess Underhill.

As more and more people cross the finish line, median times are getting slower. “In the past, it was more hard-core, serious runners finishing marathons,” explains New York Road Runners chief coach John Honerkamp. “Now, it’s the masses. It’s a bucket list item.”

THE SHIFT

So how did the marathon of elite athletes become the brass ring of bar-stool bragging rights for the rest of us?

Of course, general interest in running as a sport and social past-time has been increasing, and the masses of people taking it up (especially women, who were barely represented in the sport as recently as the ’80s and now outnumber men) want to have something to work towards.

More specifically, runners and coaches tend to point to the growth of charities using the races as fundraising tools. “It increases the accessibility of the races and markets them to people,” says Meghan Reynolds, who co-owns Hot Bird Running with Jessica Green. “Everyone wants to do good, and this way you can give to charity and do something good for yourself.”

And, of course, there’s a cool-kids-club effect. “People are inspired by their friends and family who’ve completed marathons,” Underhill explains. “They think ‘Well, if Sally can do it, I can do it.’”

“If you want to become a long-distance runner and continue to run, you shouldn’t always be in marathon training,” say Meghan Reynolds and Jessica Green.

THE DOWNSIDE?

The positive effects of the marathon boom are obvious—lots of people setting tough goals for themselves, meeting challenges while getting healthy and fit, and building community. But is there a downside?

“Some people run their first road race as a marathon, and I think that’s crazy,” says Honerkamp, who recommends starting with a race like a 5K and gradually increasing your race distance as you become more experienced.

Most seasoned runners and coaches agree, because running newbies tend to underestimate the stress the training will put on their bodies and don’t spend the time to build mileage gradually in a smart, safe way.

Reynolds and Green say that many of their clients come to them because they tried to train on their own, or too quickly, and were injured. “We believe everyone can run and achieve that distance, but it’s a lot on your body. We always say, ‘You have to respect the distance!’” —Lisa Elaine Held

Article originally appeared at:

Tapering? Wrap It Up With a Burst

In the days before a race, scale back on mileage but not instensity.

In principle, tapering should be simple–run less so you’re rested for race day. In practice, many athletes find two to three weeks of cutting back on mileage and intensity makes their legs feel heavy and lifeless. But Spanish coach and physiologist Iñigo Mujika, a leading expert on tapering, sees a way around that problem. Mujika suggests athletes start their taper early, scaling back on mileage but not intensity, then three days before the event, “reload” their muscles with an interval workout. Performing these workouts when your legs are fresher than they’ve been for months can actually increase your fitness.

Indeed, too much rest or slow running lowers the muscle tension in your legs, says Norwegian Olympian and 13:06 5-K runner Marius Bakken, which is why they feel flat and sluggish. Short, fast bursts of running raise muscle tension back up. If you get your taper right, your body will respond by producing more oxygen-carrying red blood cells, lowering stress hormone levels, and storing more fuel in your muscles–enough to shave about three percent off your finishing time, on average. Here’s how to inject some energy into your taper so you shed fatigue and sharpen your edge.

Plan it: For a marathon, cut mileage to 80 to 90 percent of normal three weeks out; reduce to 60 to 70 percent two weeks out, and 50 percent in the final week. Maintaining intensity is crucial to avoid losing fitness, so don’t slow your easy runs down; for hard workouts, do fewer intervals than you normally would but run them at your usual pace. Stick to one day off: The volume reduction should come from shorter, not fewer, runs. If you’re racing a 5-K or 10-K, reduce the length of your runs so your total mileage the week before race day is about half of your typical number.

Reload it: In the final week, for a Sunday race, take a rest day on Wednesday. Over the next three days, reload by running an interval workout at goal pace, an easy run, and an easy run with strides. For your interval run, simply modify sessions that you’ve been doing all along and resist the temptation to blast repeats faster than usual because your legs are fresh. The easy runs serve to get your legs back into the rhythm and feel of running. Aim to run at your usual pace for half your typical easy-run length, but if your legs feel heavy, add an extra mile and pick up the pace toward the end.

Turn It Up

A reload plan for the last few days before your big event

Wednesday

Marathon reload: Off

5-K or 10-K reload: Off

Thursday

Marathon reload: 2 x 1 mile at marathon pace with 2:00 rest; 4 x 400 at 10-K pace with 90 seconds rest

5-K or 10-K reload: 800 meters at 10-K pace; rest 45 seconds; 300 meters at 5-K pace; rest 2:00. Repeat sequence three times.

Friday

Marathon reload: 4 miles easy

5-K or 10-K reload: 4 miles easy

Saturday

Marathon reload: 4 miles easy; 4 x 30-second strides at 10-K to half-marathon race pace

5-K or 10-K reload: 3 miles easy; 5 x 100 meters at mile to 5-K pace

Sunday

Marathon reload: 26.2

5-K or 10-K reload: 5-K or 10-K

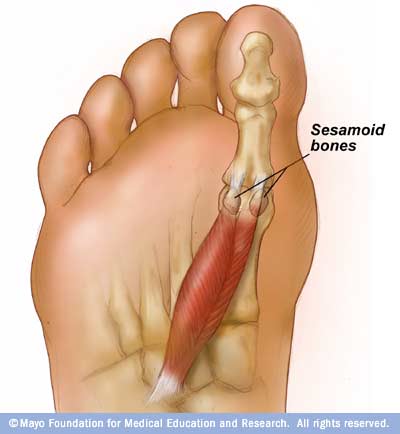

Running with sesamoiditis: How I resolved a 10 year injury by ditching my traditional running shoes.

I was asked to discuss this topic from a reader and ironically this is the injury that plagued me for 10 years before I finally learned how to run. Sesamoiditis is a condition where the two small bones of the great toe joint become inflamed. This can be the result of what is termed a bipartite sesamoid bone(referring to two bones that have not united into one during develop) or one that has become fractured. A debate exists amongst the literature as to whether a fracture truly occurs to this bone, and if so can it reunite or heal. Symptoms present with sesamoiditis include pain and swelling to the bottom or plantar aspect of the great toe joint. A sharp piercing feeling is sometimes described and one usually will limp or walk with pressure on the outside (lateral) aspect of the foot to avoid pain. The condition can go on for months and sometimes does not respond to rest or padding. It is very common amongst volley players or sports that entail forceful jumping or exploding off of the ball of the foot.

So here’s my story. I was just starting residency and had ran most of my life at that point. I had done 3 marathons and numerous other types of races and really just ran as a means of relaxation. In the year 2000, I developed pain in my right great toe in the region of my sesamoid bones (for those not understanding what they are, i’ll explain shortly). Initially I attributed it to playing ice hockey and my skates were tight and it placed increased pressure to the great toe joint. The problem was, it never resolved. After living with it for about 4 years, it finally cultivated in the winter of 2003 when I was on a run in the wintery snow of Erie, PA and the pain became so severe I could barely run. I had x-rays taken of my foot and found in addition to the bipartite tibial sesamoid knew I had, I now had a fractured fibular sesamoid to go along with it! I wore a boot for 3 weeks, and had to stop running. It never worked. It calmed it down and eventually I was able to run again, but the pain in this region persisted. I had worn holes out to the great to region in the fabric on the insides of my Birkenstock Clogs that I would operate and work in. Was I putting too much pressure here? I just figured I was limping from the pain and the region was wearing. I continued to run. I would have good months, and bad months. Eventually I went on to run several more half marathons, another full marathon, and other road races. My foot still hurt. I would try multiple custom orthotics, OTC semi-custom orthotics, and even various running shoes, but just couldn’t resolve it. I focused on “heel-striking” because that was what at that time I was “told” was the proper way to run. Imagine my frustration. A podiatrist, foot and ankle surgeon, who couldn’t fix his own foot. I had contemplated have the sesamoid removed but I felt that would be too destructive of a procedure because it is encompassed in the flexor hallucis brevis tendon and would create a ton of scarring and fibrosis. Not to mention that I was still able to run at times with no pain.

Notice the sesamoid on the left (lateral) is in 3 pieces and the sesamoid on the right (tibial) is in 2 pieces. (Dr. Nick’s Sesamoid Bones of right foot)

Enter 2009, the year when the questions starting pouring in about barefoot running. I was working an event for the Akron Marathon, when the owner of a local running shoe store (Vertical Runner) walked by wearing a pair of FiveFingers. I needed to put them on. I was getting bombarded with questions about them, and what better way then to have them on my feet to draw more attention to the matter. I wore them for the second half of the day with a suit and tie and fielded questions from the manny runners that walked by my booth. By the end of the evening, I had discovered that I was learning to stand differently because these shoes were killing my great toe! How could they possibly be good to run it? But that was just it. They forced me to stand differently. Had I been standing wrong in my other shoes? Absolutely, but I didn’t know it. I was wearing a pair of dress shoes that day, so of course my feet were going to hurt. But what did the shoe have to do withme standing wrong? I didn’t figure this out for at least another year.

I decided to focus a little more on barefoot running then just wearing a pair of FiveFingers. I started pulling the literature to understand this a little better. Surprisingly there wasn’t much out there on barefoot running. In fact most of it was anecdotal by an underground of runners who most would probably laugh at and never think much of it. But there was something about it. They weren’t getting injured and were running this way for years. That’s when I started pulling more and more literature on traditional cushioned running shoes. Surprisingly, there was not a shred of evidence to support prescribing these for running, foot pain, or any foot ailment that I had been treating and recommending them for. While all of this was happening, I had began transitioning to running in my FiveFingers. I will leave that story for another blog post!

After 8 weeksof transitioning, my sesamoiditis was all but gone! I just presumed it was coincidental as I had good months in the past, but never this long. How could this be? The treatment for sesamoiditis is to cushion the 1st MPJ, use a cut out offloading orthotic, or not run at all and rest it. I was, for all intensive purposes, running barefoot and mine resolved! Fast forward 5 months and I now completed a half marathon in a pair of FiveFingers and my sesamoiditis was 100% painfree.

Was it the shoes? Nope. I learned how to run. After another year or more of reading, learning (world wide collaboration of runners and physicians including Mark Cuccuzzella, Dan Lieberman, and Irene Davis) and now lecturing on this fascinating topic, I had finally got it. It has nothing to do with the shoes. It’s how you run. Yes I had strengthened my feet beyond what they had ever been my whole life, but the form I had now grown accustomed to was what was helping me.

So what does this have to do with fixing my sesamoiditis specifically? I took the pressure off of that area. This happened through a multitude of ways, but one that I think is most crucial is eliminating what most podiatrists and biomechanists used to describe as the “propulsion phase” of the gait cycle. By adapting a midfoot/forefoot strike pattern, with shorter strides,and landing with your foot below your body, the force that gets generated to the MPJ is reduced. You no longer pro-pulse with the great toe joint, but instead you drive forward with your thigh and the foot gets picked off the ground. There is a slight push off occurring with the foot, but its through the entire foot, not just the MPJ. So basically instead of pushing off with only your great toe, the entire foot takes the load minimizing the stress to great toe joint. This reduction in stress and force can allow the flexor hallucis longus and brevis tendons in the great toe joint to heal if they were inflamed which we typically refer to as sesamoiditis. This makes the condition more consistent with a tendonitis then a true boney pathology which can explain why many don’t respond to just simply resting the foot.