Do I have an Ingrown Toenail?

An ingrown toenail can either be infected, or just a curvature of the nail plate that is causing pain to the adjacent nail fold (skin).

Not Infected

Infected

Severely Incurvated nail

Thick nail most likely due to trauma or fungus

Treatment Options.

If the skin next to the toenail is red, inflamed, and draining, we advise you to be seen within 1 to 2 days for treatment. In the meantime, soaking in warm water with anti-bacterial soap or epsom salts for 15 minutes several times will help facilitate drainage of the infection and keep the area clean. The area should then be covered with a band-aid.

Toenail Surgery.

If the surrounding skin is infected, the portion of the nail plate needs to be removed to resolve the infection. Antibiotics are typically not necessary unless the patient is severely infected or if the patient is considering surgery to permanently remove the nail border.

There are two types of procedures for an “ingrown” toenail:

Total Nail Removal.

Sometimes a toenail becomes so painful and deformed that the best treatment option is to remove the toenail permanently. This typically involves a nail that has become so severely infected by fungus, or nail that has suffered irreversible damage from trauma. The procedure is the same as a matrixectomy, except we remove the entire toenail plate. After the area has healed, the nail bed that is exposed it not sensative, appears smooth and clean, and most of all is not painful. For cosmetic purposes, an artificial nail can be applied, or the skin can simply be painted with nail polish.

PreOp

3 months after surgical removal

What type of Recovery is involved?

Recovery involves soaking the toenail in warm water and either epsom salts or antibacterial soap for 20 minutes twice a day. The nail is then covered with a band aid and neosporin. MIssing work is usually not necessary and we allow our patients to begin exercising again in 24 to 48 hours. Please realize that this does vary with each individual patient.

For Runners?

I typically let runners run within 24 hours after a toenail avulsion. Surprisingly it is less painful after the procedure then before when the nail is ingrown. The incurvated nail border is like having a foreign body in your toe and you can imagine the relief when it is removed.

I probably use his example more then anything when discussing improving speed and heart rate training. Why Lance? Not because he was “cheating” or using enhancing agents, but how doing this makes him faster. Consider, Armstrong did not implant mechanical legs or motors into his body to make his legs turn faster in order to get faster on his bike. What he did do was blood doping to improve his efficiency. Are you following me? When our bodies can deliver oxygen to our muscles and organ systems more efficiently, we can run or bike faster. Most of the time when it comes to endurance athletes training for a half marathon or marathon, they try to “run faster” to get faster. They already have the speed, they just need endurance. For example, if you can run an 8 minute mile, but your half marathon pace is 8:30, then you have the speed but need the endurance.

How do we build endurance? Not by doing what Lance did, but by improving our efficiency through endurance training at a slow aerobic pace. Long slow runs will build endurance which can help one keep their “speed” over an endurance race. For more information on heart rate training, see some of my other posts.

https://drnicksrunningblog.com/category/heart-rate-training-2/

Plantar fasciitis is an epidemic amongst our society and has resulted in numerous treatment plans that vary from one health care provider to another. Guidelines for treatment protocols exist and even those differ from one specialty to another. Plantar fasciitis is searched monthly on google over 550,000 times with web pages revealing information ranging from explaining the cause to sites marketing gimmick treatment devices to take advantage of those suffering in pain.

The purpose of this post is to give hope to those suffering and hopefully point runners in the right direction who are trying to overcome this chronic condition.

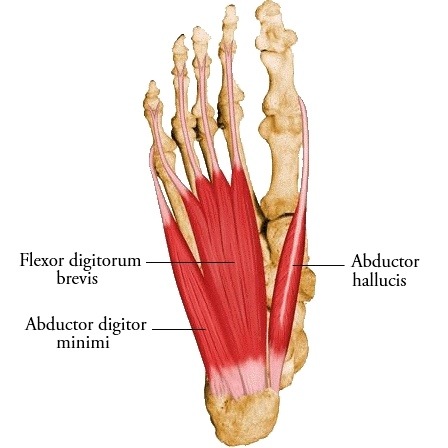

To begin, plantar fasciitis has been described as an inflammation of the plantar fascia – a band of tissue that originates on the heel bone and fans out to the toes of the feet providing structure and protection to the underlying vessels, nerves, and muscles of the foot. Surprisingly, studies have demonstrated inflammatory cells are not present within the plantar fascia in those suffering from the condition suggesting it may not be “inflammation” within the plantar fascia. There are 3 muscles that attach to the heel bone in conjunction with the plantar fascia – the abductor hallucis, abductor digiti minimi, and flexor hallucis brevis. These muscles develop tendonitis when overused or weak from being in shoegear all day. This leads to pain upon arising in the morning, and again throughout the day after increased activity.

The muscular tissues that are inflamed are attempting to heal themselves and need to be stretched or warmed up to reduce the pain. Then, after periods of activity, the muscles again become sore leading to pain later in the day. The result – chronic pain to the heel and or arch area.

When runners develop plantar fasciitis, what should they do?

In my practice, if they are able to complete a run without pain, I encourage the patient to continue running. I then advise:

1. anti-inflammatories if they are able to take them

2. Stretching exercise to be performed 4 times a day

3. Ice 30 minutes as many times a day to the area

4. Barefoot activities 20-30 minutes per day to encourage foot strengthening gradually increasing weekly

5. Flat shoes without a heel to promote anatomic positioning of the foot and rest of body

6. Splinting may be done but only temporarily

If the condition persists, cortisone injections are utilized to aid in decreasing the inflammation. They are safer in theory then NSAIDS as they are local and not systemically absorbed.

If the above treatment fails, then the condition is most likely secondary to the runner’s form which will need to be analyzed and changed. I simply tell patients who have tried all of this and failed, then something they are doing at home, work, or while running is precipitating the condition.

Orthotics are not the answer for my patients who are runners as they simply promote weakening of foot musculature.

What about a plantar fasciotmy? (Surgical release of the plantar fascia)

To reiterate, studies show that after performing a plantar fasciectomy (surgical release of the plantar fascia) the tissue sent to the pathologist revealed no inflammatory changes. This leads many practitioners to believe the condition is more muscular which explains the pain upon rising in the morning or after periods of rest. Why then would cutting the plantar fascia be indicated to help overcome this condition? As a surgeon, I stopped doing this procedure several years ago as the studies do not advocate it’s relevance.

Consider this, why would we cut an anatomic structure that process structural integrity to the foot, protects the underlying vessels, and is not even scientifically proven to be inflamed in clinical studies?

Therefore, treat this like a tendonitis.

It’s the time of the year when everyone sets their goals of losing weight and becoming fit. Some do P90X, Insanity, Cross Fit, or simply just join a gym to accomplish these tasks. Running tends to be a fitness activity that is easy to do, can be done almost anywhere, and is rather inexpensive. What tends to stop most individuals from continuing to run is overuse injuries or pain. This is typically due to improper training regimens. Our society has the belief that no pain equals no gain, so we push harder thinking we will get more benefit from the workout. While this can be true some of the time, if most workouts are done at maximum potential this can lead to negative effects such as injury and the inability to improve aerobically.

One of the key points to understanding this comes from realizing how our bodies utilize energy. One of the sources of fuel our body uses is glucose which we obtain from glycogen stores in our body. Glucose is the secondary source of long term energy storage in our body (the primary energy stores being fats held in adipose tissue). At all times our body is using both glucose and fats for energy with the key being the right ratio. Elite marathoners have trained themselves to burn primarily fat for the majority of the race leaving glucose for the secondary fuel source. The reason is that we only have enough glucose at hand for about 60 minutes of intense activity at which point we will have to rely on external sources of glucose. When we ingest supplemental glucose some is used for energy and some gets stored because as we ingest glucose our bodies release insulin which functions to store the glucose. By training slower over longer durations our body becomes efficient at utilizing fat thereby reducing the need for external sources of glucose. This leads to burning more fat.

Consider that when one exercises at maximum potential for one hour, they will most likely primarily burn glucose. At exhaustion glucose utilization initially decreases more than glucose production, which leads to greater hyperglycemia, requiring a substantial rise in insulin for 40–60 min to restore pre-exercise levels. So little fat if any gets burned, insulin levels ultimately rise resulting in storage of more glucose that will be converted into glycogen. Only so much can be stored as glycogen and the rest is stored as fat.

So if you want become more fit, reduce your risk of injury, and burn more fat – turn to long slow runs of moderate exertion over periods of up to 60 minutes. Exertion levels can be better understood by training according to your heart rate. See my blog on heart rate training –The Maffetone Method for Running: How slowing down can make you faster. Need a heart rate monitor? . Click here for an inexpensive yet reliable heart rate monitor.

I have blogged about these shoes before but I couldn’t help sharing my thoughts again. The Vibram Lontra has changed winter running for me. OUTSTANDING!! I just completed a two hour and forty-six minute run in snowy weather (3-6 inches non stop snowing) and my feet are warm, dry and happy!! The heavy duty tread kept my traction going up and down hills and still provided cushion. I typically will not run more then 2 hours in FiveFingers but the added cushion helped. My light weight Injinji toe socks were thin enough to not create too tight of a fit and they were completely dry upon completing my run. In fact, when comparing my feet to my wife’s feet (who was sporting a pair of New Balance Minimus Trail shoes)- her’s were red and numb while my were healthy and normal color!!

It’s great knowing I can still head out in extreme conditions and still keep my feet warm, dry, and remain free and mobile!!

Those familiar with my posts and articles may have heard me say, “If your able to run an 8:00 mile, you already have the speed. To run this 8:00 mile for 26 miles, you need endurance.” Obviously you can plug any number into that mile pace, but the point is many people run faster thinking they will “get faster”. This does not necessarily hold true for distance running. In fact I will even include a 5k in the category of distance running. The point is, once you have your speed for a goal pace, you need the endurance to carry you over a distance. This can best be accomplished through runs known as tempo runs. Tempo runs improve your body’s ability to get rid of lactic acid making you more efficient. There really is no need to spend months at the track to get faster. Unless, of course, you enjoy running in circles.

Below is an article I read which I felt may be helpful. Enjoy!

Your Perfect Tempo

Robin Roberts runs like a Kenyan. Okay, she doesn’t run as fast as a Kenyan, but the 47-year-old New York City advertising executive–who trains far from Nairobi–has achieved personal records by using the same workout that has helped propel the likes of Paul Tergat and Lornah Kiplagat to greatness. The secret? A tempo run, that faster-paced workout also known as a lactate-threshold, LT, or threshold run.

Roberts–who’d dabbled in faster-paced short efforts–learned to do a proper tempo run only when she began working with a coach, Toby Tanser. In 1995, when Tanser was an elite young track runner from Sweden, he trained with the Kenyan’s “A” team for seven months. They ran classic tempos–a slow 15-minute warmup, followed by at least 20 minutes at a challenging but manageable pace, then a 15-minute cooldown–as often as twice a week. “The foundation of Kenyan running is based almost exclusively on tempo training,” says Tanser. “It changed my view on training.”

Today, Tanser and many running experts believe that tempo runs are the single most important workout you can do to improve your speed for any race distance. “There’s no beating the long run for pure endurance,” says Tanser. “But tempo running is crucial to racing success because it trains your body to sustain speed over distance.” So crucial, in fact, that it trumps track sessions in the longer distances. “Tempo training is more important than speedwork for the half and full marathon,” says Loveland, Colorado, coach Gale Bernhardt, author of Training Plans for Multisport Athletes. “Everyone who does tempo runs diligently improves.” You also have to be diligent, as Roberts discovered, about doing them correctly.

Why the Tempo Works…

Tempo running improves a crucial physiological variable for running success: our metabolic fitness. “Most runners have trained their cardiovascular system to deliver oxygen to the muscles,” says exercise scientist Bill Pierce, chair of the health and exercise science department at Furman University in South Carolina, “but they haven’t trained their bodies to use that oxygen once it arrives. Tempo runs do just that by teaching the body to use oxygen for metabolism more efficiently.”

How? By increasing your lactate threshold (LT), or the point at which the body fatigues at a certain pace. During tempo runs, lactate and hydrogen ions–by-products of metabolism–are released into the muscles, says 2:46 marathoner Carwyn Sharp, Ph.D., an exercise scientist who works with NASA. The ions make the muscles acidic, eventually leading to fatigue. The better trained you become, the higher you push your “threshold,” meaning your muscles become better at using these byproducts. The result is less-acidic muscles (that is, muscles that haven’t reached their new “threshold”), so they keep on contracting, letting you run farther and faster.

…If Done Properly

But to garner this training effect, you’ve got to put in enough time at the right intensity–which is where Roberts went wrong. Her tempo runs, like those of many runners, were too short and too slow. “You need to get the hydrogen ions in the muscles for a sufficient length of time for the muscles to become adept at using them,” says Sharp. Typically, 20 minutes is sufficient, or two to three miles if your goal is general fitness or a 5-K. Runners tackling longer distances should do longer tempo runs during their peak training weeks: four to six miles for the 10-K, six to eight for the half-marathon, and eight to 10 for 26.2.

Because Roberts was focusing on the half-marathon, Tanser built up her tempo runs to eight miles (plus warmup and cooldown) at an eight-minute-per-mile pace. “The pace was uncomfortable,” she says. “But after a while I realized, ‘Oh, I can maintain this for a long time.'”

That’s exactly how tempo pace should feel. “It’s what I call ‘comfortably hard,'” says Pierce. “You know you’re working, but you’re not racing. At the same time, you’d be happy if you could slow down.”

You’ll be even happier if you make tempo running a part of your weekly training regimen, and get results that make you feel like a Kenyan–if not quite as fast.

UP TEMPO

A classic tempo or lactate-threshold run is a sustained, comfortably hard effort for two to four miles. The workouts below are geared toward experience levels and race goals.

GOAL: Get Started Coach Gale Bernhardt uses this four-week progression for tempo-newbies. Do a 10- to 15-minute warmup and cooldown.

Week 1: 5 x 3 minutes at tempo pace, 60-second easy jog in between each one (if you have to walk during the recovery, you’re going too hard).Week 2: 5 x 4 minutes at tempo pace, 60-second easy jog recovery Week 3: 4 x 5 minutes at tempo pace, 90-second easy jog recovery Week 4: 20 minutes steady tempo pace

GOAL: 5-K to 10-K Run three easy miles, followed by two repeats of two miles at 10-K pace or one mile at 5-K pace. Recover with one mile easy between repeats. Do a two-mile easy cooldown for a total of eight or 10 miles.

GOAL: Half to Full Marathon Do this challenging long run once or twice during your training. After a warmup, run three (half-marathoners) or six (marathoners) miles at the easier end of your tempo pace range (see “The Right Rhythm,” below). Jog for five minutes, then do another three or six miles. “Maintaining that comfortably hard pace for so many miles will whip you into shape for long distances,” says coach Toby Tanser.

The Right Rhythm

To ensure you’re doing tempo workouts at the right pace, use one of these four methods to gauge your intensity.

Recent Race: Add 30 to 40 seconds to your current 5-K pace or 15 to 20 seconds to your 10-K pace

Heart Rate: 85 to 90 percent of your maximum heart rate

Perceived Exertion: An 8 on a 1-to-10 scale (a comfortable effort would be a 5; racing would be close to a 10)

Talk Test: A question like “Pace okay?” should be possible, but conversation won’t be.