Today my blog received its 10,000 hit for the month and 50,000 hits since it stated 10 months ago. I wanted to personally thank everyone for reading and for providing comments. While these numbers might not be astronomical for the blog world, it means a lot to me to be able to help runners outside of my practice simply by reading this blog. I’d like to think that with the way digital media is advancing, things are just getting started for me in the world of blogging and treating people online.

Below is a comments box and I welcome questions, thoughts, or topics you would like me to discuss. If your suffering from any running injury -plantar fasciitis, IT band syndrome, piriformis syndrome, hamstring strain, shin splints, knee pain, condromalacia, or neuroma to name few, feel free to ask. I do my best to respond to tweets regarding running injuries and I would like to provide more detail to my readers here.

Thanks again!

Dr. Nick

I recently read an article published in Running Times discussing injury patterns amongst elite athletes. The bottom line was that if you run and push yourself to improve times and be more competitive, then injury is expected. Really? Should a conversation about marathon training always contain the following – plantar fasciitis, IT band syndrome, piriformis syndrome, hamstring strain, shin splints, knee pain, condromalacia, neuroma, and so on? No wonder why so many people tend to think runners are “crazy”! And have you ever heard someone say, “I’m not built to run”, or “I can only do the elliptical because its easier on my knees”? There’s actually a study published demonstrating an increase in force to the knees in while using an elliptical.

Running is natural.

It is a gradual progression from walking where both feet are on the ground together to a single legged activity of nothing more then jumping, or as Mark Cucuzzella, MD describes “engaging the spring”. If its so natural, then why are injury rates as high as 70% a year amongst recreational runners? That’s a question that many physicians, coaches, and exercise physiologists have been trying to answer for years. It becomes a very difficult process to study because of the extreme variables that exist amongst runners. Consider that elite runners train 80-110 miles a week many times running twice a day. When you try to compare causes for their injuries to a recreational runners who does maybe 20-30 miles a week, there are no relationships that could be considered credible. In other words it would be very easily disputed and not published. Other variables include ones body type, their foot structure, shoe selection, orthotics, intensity, form and fitness level to name a few.

What is my approach to this complex problem?

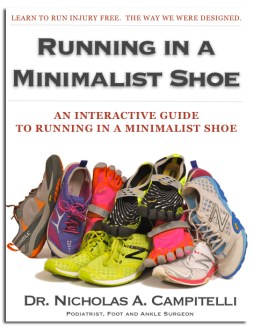

Don’t make it so complex. Start slow. Gradually increase mileage according to the 10% rule each week. Walk/running is great for starting out. A hear rate monitor will also bring you to reality with how fast you should be going. Learn to midfoot or forefoot strike much like you would if you were to run in place. My $1.99 text offers high quality video demonstrating this. (I’m not a salesmen so don’t take this as a pitch! Much of what is in that book text wise can be found on my blog. It does offer a simple read with video explanation for those using an iPad though.) Secondly, when choosing footwear, it should allow your foot to be mobile and feel the ground. I’ve been quoted as saying, “a shoe should allow you to run, not enable you to run”. There is no true data to suggest runners should be wearing motion control shoes to prevent injury. A shoe is like the shirt on your back when it comes to preventing injury. Most importantly, listen to your body, not the log. If the log has you going 3 miles and you feel awesome, you may be able to to 5 or 6 that day. Conversely if you are exhausted, missed sleep, and have a big day, you may need to skip the run. Something I tell many runners when training for a marathon, or even half marathon, log slow, slow miles. We know that from following your heart rate fitness will improve regardless of your pace. When you push you pace to try to become faster, this is a recipe for disaster. You may feel good for one mile, but your body will be compensating for each step of every mile that follows increasing risk for injury. Something else to consider is that you become a better runner by running more. A 3 day a week running program isn’t always best to avoid injury, especially when training for a marathon. The body isn’t being prepped for the long runs. Gradually building to increase your days and miles slowly will reduce the likelihood of becoming injury by adequately conditioning the body. Preceding and following a long weekend run with slow easy runs is much better then taking a day off before and after. Remember slow and easy is the key. If you feel too fatigued you’re either going too fast, or you do need rest. Even if you walk a bit of these runs it’s ok.

So sometimes the best program to follow is the one you create. Until you have developed into a runner that is seasoned enough to run injury free, don’t add speed workouts. Build the endurance engine and your speed will follow all while becoming injury free. How many miles a week? As many as you want as long as you build by the rule of 10%. Should you run 7 days a week? I prefer 6 but if you’re going easy 7 could be fine. Don’t get cut up with what’s on paper! A final thought. Running should be fun. If its not, then you’re probably doing it wrong.

When it comes to running on the treadmill, most people find it boring, torturous, and would rather be outside where they can get a “better” workout. Here is something to consider that may actually help you feel better about that run you need to get in on the treadmill. For those of you who follow my blog, you probably already know that I’m a firm believer of heart rate training. It’s really the only objective way you can track your progress and conditioning while at the same time greatly reduce the likelihood of overtraining or becoming injured. If you haven’t read any of my other blog posts, here is one discussing Maffetone’s method to heart rate training you probably should read.

When you first begin to understand your perceived effort with heart rate training, you will realize that when you are on a treadmill, you tend to run at with a faster rate at a given heart rate then you do outside. This is usually due to the lack of wind resistance as well as the absence of hills. While many see this an insufficient workout or run, here is something to consider. When you are training at your aerobic rate outside, your pace will actually be slower (Maffetone describes this as being 180-age in BPM and will build endurance and improve conditioning most efficiently without over exertion. Over exerting can lead to longer recovery times and overtraining/injury). On the treadmill, this same aerobic rate will have you running a bit faster (sometimes 30 seconds per mile) and get your legs used to the quicker turnover at an overall lower HR then you would be experiencing while running outside. So your legs are getting a “speed” workout without overtaxing the cardiovascular system. Maffetone describes doing speed workouts downhill for the same reasons- the legs get used to faster turnover rates while the heart and cardiovascular system does not get overtaxed. The best of both worlds!!

Entering my 9th year of practice I’ve noticed something rather common amongst patients I see complaining of generalized foot pain. It’s the phrase, “I’ve tried several different pairs of shoes, and nothing seems to work”. We live in a society that believes in order for us to have healthy feet, we need to have “good” shoes. The question then becomes what is a good shoe? Is it a $200 running shoe? A $300 dress shoe hand crafted with Italian leather with a 3/4 indestructible heel? Don’t forget the ever popular saying, “you get what you pay for”. Not exactly when it comes to shoes. At least when your looking at pain relief.

Consider the function of a shoe.

Really, it only serves to protect the foot, not enhance it. Irene Davis, Director of the Spaulding National Running Center at Harvard Medical School, provides an outstanding lecture on barefoot running and shoes (which can be seen here) where she agrees that shoes really only serve to protect the foot. What is it providing protection from? Mainly the environmental factors- stones, rocks, rough surfaces, cold or hot surfaces, and pretty much anything that can damage your skin.

What if you have an injury like plantar fasciitis?

This is the topic of another subject where I could write for hours (if not days). A shoe can be considered necessary when initially treating plantar fasciitis, but really its only to “splint” the foot. Simply put it should give those tired muscles a break. The shoe could be a cushioned running shoe, a cam walker, or even a cast. The function is to give the foot musculature a break and allow healing to occur. NOT SUPPORT THE FOOT FOR LONG TERM. This is where our society has yet to understand the function of a shoe. There exists a stigma that enables most individuals to think shoes need to support our feet or they can’t function without a “supportive” shoe. In other words, we don’t give out feet any credit and basically set them up for failure by inferring that the feet alone can’t support our body. Isn’t that what they were designed to do?

What shoes should I wear?

This is a question I cannot answer. I can however advise you what you shouldn’t wear. A shoe should not be rigid in any manner, it should not “support” the arch, and it should allow all motions that can occur in the foot to occur. This may come as a shock to most people, but remember, before the 70’s, the shoes that you shouldn’t wear don’t exist.

“A shoe should allow you to run, not enable you to run.”

-Dr. Nick

As I’m dreading a 10 mile tempo running tomorrow morning because we are still getting hit with snow, I came across this outstanding article published on Runner’s World website. It’s a great read that gives some wonderful ideas for treadmill workouts. I’ve come to the conclusion that running 10 miles fast at 5am in a 3oz pair of New Balance RC5000s on snow covered roads is not going to happen!!

How Real Runners Train on Treadmills

Treadmill workouts for any occasion

By Phil Latter

Published December 13, 2011

Everyone has their winter war stories. There’s the day your goatee froze before you made it down the driveway. The time you broke through an icy creek but finished your 15-miler anyway. And who can forget the Blizzard of (insert year here), when you tackled the pelting corn snow and zero visibility to get in that precious hour run. Each and every winter tale ends with a storybook conclusion: “It’ll make me tougher on race day.”

Yet what if that resolve to fight the elements is actually lessening your ability to compete when it matters most? Specificity is, after all, a tricky beast to tame when the wind chill is minus 25 and you’re skating your way down Main Street in four layers of tights. The solution to your winter woes? The thing your “tough gal” persona uses as a coat rack in the basement: a treadmill.

The perception of the treadmill as the domain of beginners is outdated. Its ability to simulate courses and produce exact paces in a controlled environment gives it a decided advantage over outdoor junk miles. It’s why Olympic runners and their coaches have embraced the machine for years.

I spoke with five elite runners and coaches to find their favorite treadmill workouts and the purpose behind them. With everything from tempos to hills to long runs, you’re certain to find something to keep you inside during the long months ahead.

INCREASING PACE TEMPO

Advocate: Kara Goucher, 2008 Olympian at 5,000m and 10,000m

The Workout: 6-mile tempo run starting at threshold pace and finishing close to 10K pace

It’s pragmatics, not passion, that drives Kara Goucher to the treadmill. “I would absolutely prefer to be outside,” she says, despite having the luxury of an AlterG treadmill in her home. But the early sunsets of Portland winters can make outdoor running dangerous at times. Which isn’t to say that Goucher doesn’t recognize treadmill running has its own set of perks. “Sometimes workouts go by quicker because the treadmill does the thinking for you,” Goucher says. “For instance, in a tempo run, you don’t have to think, ‘I need to pick it up now’ or ‘I need to hold this pace.‘ You just set the treadmill and zone out because you’re just trying to stay on it.”

That thinking framed one of Goucher’s key workouts before heading to South Korea for this year’s world championships. Setting the machine at her current anaerobic threshold pace, Goucher ran a solid tempo run before finishing at her current 10K pace. The workout taxed her just as coach Alberto Salazar hoped, but also ensured that Goucher’s competitive juices were kept in line.

Your Turn: Simple but effective, this traditional (3-to 6-mile) tempo run adds the element of a faster (but not all-out) last mile into the mix. Whereas the allure of sprinting down the backstretch might sneak up on you outdoors, here you know the workout won’t be sabotaged by over-eager legs (as long as you don’t play too much with the speed buttons). “There are times where you might push too hard outside,” Goucher says. “On the treadmill you can control that.”

RELATED ARTICLE: Other Great Treadmill Workouts

TREADMILL LACTATE FLUSHING SESSION

Advocate: Marius Bakken, Norwegian record-holder in the 3,000m and 5,000m, coach at marathon-training-schedule.com

The Workout: 30 minutes to 2 hours of varying pace with quick recoveries

There are those who use treadmills. Then there’s Marius Bakken. During his prime, the two-time Olympian with a 5,000m PR of 13:06 ran every single hard workout from October through April on a treadmill, except when he was training in Kenya. During summers he continued to do half of his sessions running in place. “I was never really forced to run on the treadmill,” he says. “Despite cold winters in Norway it is always possible to find some stretches with bare asphalt.”

If such treadmill devotion seems a bit extreme, such is the nature of Bakken. He performed more than 5,000 lactate threshold tests during his career, adjusting workout paces on the fly to match his blood results. Ever the scientist, Bakken had one favorite workout that combined elements of all the energy systems in one treadmill-specific session.

Using his current lactate threshold as a starting point (roughly 25K race pace in his case), Bakken would float up and down in speed at predetermined intervals, going as fast as 4-mile race pace while recovering no slower than his marathon pace plus 10 seconds per mile (MP + :10). While the workout teaches pace control and works muscles in a number of ways, Bakken believes the biggest gain comes from keeping the recovery portions of the run up-tempo.

“You get a flushing effect of the lactate [system] when you go somewhat down but not all the way down to recovery pace,” he says.

Your Turn: Taking your most recent race results as a starting point, use a pace calculator such as the ones found at runningtimes.com or mcmillanrunning.com to get an estimate of your paces for a variety of races; then translate those to miles per hour on the treadmill. From there, start close to your 25K race pace and weave your way up and down in speed, making sure never to recover too slowly.

Bakken gives this example: 3 minutes at 25K pace; 2 minutes at MP + :10; 1 minute at 10K pace; 2 minutes at MP + :10; 2 minutes at marathon pace; 2 minutes at 25K pace; 2 minutes at 15K pace; 2 minutes at MP + :10; 1 minute at 4-mile pace; and so on. A 5K runner might do this session for 30 minutes, a marathoner for upwards of 2 hours. “You can of course make this much simpler and have some workouts with longer periods at one pace,” Bakken says. “You’ll be surprised how much better you’ll handle this type of work after two to three workouts.” Bakken advises doing it only once per month.

THE ENDLESS UPHILL

Advocate: Pete Pfitzinger, two-time Olympic marathoner, chief executive of the New Zealand Academy of Sport

The Workout: 60 minutes or longer at a 4-to 8-percent grade

Of all the advantages a treadmill can confer on its user, perhaps the biggest is eliminating the limitations of their geographic location. This is most obvious when it comes to simulating epic climbs. Living in a part of the country where mountains are scarce can make signing up for events like the Mount Washington Road Race or Pikes Peak Ascent daunting. And even where torturously long climbs exist, the logistics (“Will someone pick me up at the top?”) can make it impractical. Today, technology can help you overcome those obstacles. “If you are running Mount Washington and live somewhere flat, you can prepare reasonably well on the treadmill,” says Pete Pfitzinger. “The key decision at Mount Washington is to ‘find your gear’ [i.e., the highest effort you can maintain] early in the race and stick to it. There is little room for error because if you go too hard there is nowhere to recover.”

Finding that gear is much more feasible on a treadmill, where all the other variables are controlled. Even then, Pfitzinger cautions trying to simulate scaling an actual mountain. “At 4 to 8 percent [grade] the stride is relatively normal,” he says, “but above that it starts to be different than overground running.”

Your Turn: Ready. Set. Climb. After setting the treadmill’s incline somewhere between 4 and 8 percent, prepare to climb long and steady for the next hour. While specifically mimicking a race course’s profile may be helpful if you’re preparing for an uphill race, make sure never to set the treadmill’s gradient to such an extreme that your form breaks down. “From my own trial and error, anything over 8 percent feels more like climbing [than running] and is hard to sustain,” says Pfitzinger.

Sorry, but this workout isn’t only for those prepping for grinds like Mount Washington. Kenyan Moses Tanui included a 22K constant climb during his training for his two Boston Marathon wins. By swapping some speed for incline, you increase the number and type of muscle fibers recruited and, therefore, improve more over the same effort on the flat.

THE LONG RUN

Advocate: Dennis Barker, coach of Team USA Minnesota

The Workout: Marathon-simulation run lasting 20 to 30 minutes longer than finishing time goal

Despite coaching full-time in the frequently arctic state of Minnesota, Dennis Barker doesn’t have his runners on the treadmill all that frequently. “One would think that I would have a lot of treadmill workouts living up here,” he says, “but the snow removal here is pretty good.” Access to indoor tracks, football practice facilities and even the 3-laps-to-the-mile Metrodome concourse give his athletes a multitude of options during the colder months.

Still, there are certain workouts that Barker finds just go better on the treadmill. Chief among these is a long run. A really, really long run. “We go 2 and a half to 3 hours,” Barker says. “Not so much at marathon pace, but they’re on the treadmill for 20 to 30 minutes longer than they would be out there in the marathon.” The simulation doesn’t end there.

“Every 15 minutes they’ll drink just like they would in the marathon,” he says. “We also try to simulate the course by putting in hills. We don’t vary the pace there; it’s just a harder effort.”

Your Turn: Thanks to sites like mapmyrun.com, the topography of almost any race course is readily available. Print out the elevation chart (which shows gradient), grab your fluids and gels, and perform one of your long runs on the treadmill, matching the race course’s terrain with your run mile for mile. Keep the pace comfortable but steady, and don’t change speeds even when elevating the treadmill bed. The course replication will have more than just physical benefits. “I think treadmill running does simulate a marathon quite well,” Barker says, “just because it’s so monotonous.”

THE HILL CIRCUIT

Advocate: Magdalena Lewy Boulet, 2008 Olympic marathoner, 2011 Falmouth Road Race champion

The Workout: 20 x 30 seconds hard climbing (with 30-second stationary rest) at the maximal gradient equivalent to mile race pace

At the Stockholm DN Galan meet in August, Magdalena Lewy Boulet ran a personal best of 15:14 in the 5,000m. If setting a 49-second PR at the age of 38 wasn’t surprising enough for the veteran marathoner, consider her training heading up to that magical day in Sweden. “All of my running was slower than 10K pace [plus] a really hard session doing hills on the treadmill,” Lewy Boulet says of her time altitude training near Lake Tahoe. “Based on that I PRed in the 5K. It obviously translates, but you’re not really running anything at that pace.”

Translating workouts to the treadmill has been a weekly staple of Lewy Boulet’s training since 2007. During the year preceding the Olympic marathon trials, she found her body incapable of handling the stress associated with speed work. “I realized if I want to compete at this level, I need to do speed work, and I can’t get it on the track,” she says. “[Coach] Jack [Daniels] said, ‘We’re going to try something different. We’re going to get a hard effort going up a hill, and we’re going to do it on the treadmill so you don’t have to come downhill.'” The end result: a spot on the U.S. Olympic team in Beijing.

Since that time Lewy Boulet has become a full-blooded treadmill convert. “It’s a huge factor in terms of recovery and injury prevention,” she says. “It allows me to really stay healthy for a huge chunk of the year. It just doesn’t beat me up as much as cranking out really intense work on the track.”

Your Turn: Without a degree in physics, it might seem daunting to match your current pace with its associated effort at a higher gradient. Luckily, resources such as the book Daniels’ Running Formula and the website hillrunner.com offer charts that approximate this well.

For instance, using the Daniels’ Running Formula chart, a 5:00 miler whose treadmill goes up to 10 percent gradient would set the treadmill at 7.5 mph to achieve the desired workout. Alternate 30 seconds of hard running with 30 seconds recovery on steady ground. Use the treadmill’s side rails to swing your body off the machine during the recovery period (“That’s how I get my upper body strength work,” Lewy Boulet jokes) and to pull yourself back on during the hill portion. Don’t let go until you’re confident you’re up to speed.

The hills may be steep, but the pace is forgiving on the body, says Lewy Boulet. “It’s a good way to walk away from a workout saying, ‘Oh, my God, that was easy on my legs, but wow my lungs were working really hard.'”

The 1% Debate

Run on a treadmill long enough and you’re sure to hear some well-meaning fellow runner tell you to raise your machine to a 1-percent grade. Why?

To offset the lack of wind resistance. Run on the flattest setting, they’ll say, and you’ll be cheating yourself.

It may sound like solid advice in the gym, but is the all-encompassing 1 percent rule an old wives’ tale for mechanized running or a truism backed by scientific fact? Researchers at the University of Brighton in the United Kingdom wondered the same thing 15 years ago, so they tested a group of trained runners on treadmills and an outdoor track, measuring their signs of exertion. “The energy cost of running outdoors is always greater than running indoors whatever the pace,” says Jonathan Doust, Ph.D., one of the study’s authors. “The faster you run the greater the effect.”

This is most clearly seen in the tactics of races like the Tour de France, where the peloton saves energy by sharing the cost of breaking the wind. “At the slower speeds of running the effect of air resistance is much less, but still measureable,” Doust says. For instance, running at a pace of 6:00/mile outdoors will add 5 percent to the total energy cost due to wind resistance. This would show up as roughly five extra beats per minute on that runner’s heart rate.

As springtime rolls around, many people will be starting a training program for marathons, half marathons, 5ks, etc. Some will be using this as a way to lose weight and get in better shape. While it is true that running can improve your overall well being and fitness level, it does not mean that you are exempt from a “proper diet”. I have heard stories of marathon runners eating whatever they want because they “ran”. The problem with this is, your body still has to process and store the unhealthy food you are eating regardless of how far you ran or how many calories you burned.

On average, an individual who does an 18 mile training will burn roughly 2,000 calories. The total amount will vary according to many factors but that is not the focus if this post. (Pace can be a big determinant of calories burned and isn’t always more the faster/harder one runs. At an aerobic pace our bodies will burn more fat then if we run harder and force the body to utilize the small supply of glucose.) To maintain a healthy body weight, the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute recommends moderately active females consume between 1,800 and 2,200 per day while moderately active adult men require between 2,200 and 2,800 calories each day. Consider that if the average person consumes roughly 2,000 calories a day and then burns 2,000 calories on a long training run, they will have to consume twice the amount of what they typically eat that day just to maintain their weight. This person probably will be hungry all day and most likely snack more and have the mentality they can “eat whatever”. The problem with this is if the person snacks and eats readily available junk food, they will not satisfy their hunger and most likely consume far more then the extra 2,000 calories they burned.

This pattern can continue at a smaller degree during the moderate length runs during the week eventually adding up over time. Weight gain occurs when an individual consumes an excess of daily calories over a period of time. Consuming an extra 3,500 calories a week typically results in about 1 lb. per week weight gain.

Nutrition is very important when training for marathons and half marathons so focus on trying to replace the calories lost with an equal amount of healthy calories from whole foods.

This seems to be the most searched topic on google when it comes to running injuries so I figured I better address this on my blog!

What are shin splints?

Simply put, it is pain that occurs to the lower legs (shin area) that come arise from a number of different reasons. It’s a catch all term for leg pain. The pain can be due to several possible injury patterns that I will review below.

Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome (MTTS) is a condition where then deep tissue structures (specifically the deep fascia surrounding the muscles) become inflamed from stress of overuse. The theory is that it pulls on its attachment to the leg bone (tibia) causing pain.

Tibial Stress Fractures. A stress fracture can occur to the tibia (the long bone of the lower leg) and usually presents as pain that is pin point or in one specific area along the tibia. It typically hurts with walking as well during an entire run as opposed to resolving when you warm up. This is best diagnosed with an MRI.

Tendinitis. This is probably the most common cause of pain to the lower extremity that gets labeled “shin splints” by runners. Without going into an in depth anatomy lesson, think of the leg having compartments of muscles. Shin pain will usual effect the inside or medial compartment of muscles (specifically the deep posterior compartment). The posterior tibial tendon and muscle becomes overused and develops a tendonitis. Pain along the outside of the leg involves the lateral compartment and is due to overuse of the anterior tibial tendon.

Compartment syndrome. This is a more serious condition where the muscles in the four compartments become engorged with blood due to increased activity and places pressure in the nerves in these compartments. Symptoms include severe pain followed by numbness and tingling during that activity that eventually requires the runner to stop. Within 30 minutes the symptoms usually resolve. This condition usually requires surgical release of the compartments however recent literature is now suggesting by altering your running form to a more natural form with a midfoot or forefoot strike pattern can resolve the condition.

What causes shin splints?

The most common cause of shin splints is from overuse which can be to due to running too much too soon, or going too fast too often. Improper form can also lead to shin splints as it places undue stress to the leg muscles causing them to become overused.

In my practice I approach these above conditions by correcting running form, training intensity, and training patterns. Rarely if ever does a runner need a shoe orthotic to correct these injuries.

As always, if you are experiencing any of these symptoms, it is best to contact your doctor and halt your running.

Thanks for reading!

-Dr. Nick

Originally appeared on Boston.com

By Matt Pepin, Boston.com Sports

American Ryan Hall will not participate in the 2013 Boston Marathon, race sponsor John Hancock Financial announced on Wednesday.According to a press release, “Hall missed crucial training due to a quadriceps strain.” Hall holds the American record at the Boston Marathon, a 2:04.58 in 2011.

Hall has been hampered by injuries in the last year. He dropped out of the Olympic marathon in London because of a hamstring strain and did not compete in the New York City Marathon in November because of a quad strain. He did not run in the Boston Marathon last year because he was training for the Olympics.

Other previously announced elite male runners who have also cancelled because of injury include Moses Mosop, Shami Dawit, Eric Gillis, and Lucas Rotich. Two elite women also dropped out due to “lack of fitness” – Asefelech Mergia Medessa and Karolina Jarzynska.

Three runners were added to the elite field: Tirfi Tsegaye Beyene, Lelisa Desisa Benti, and Laban Korir.